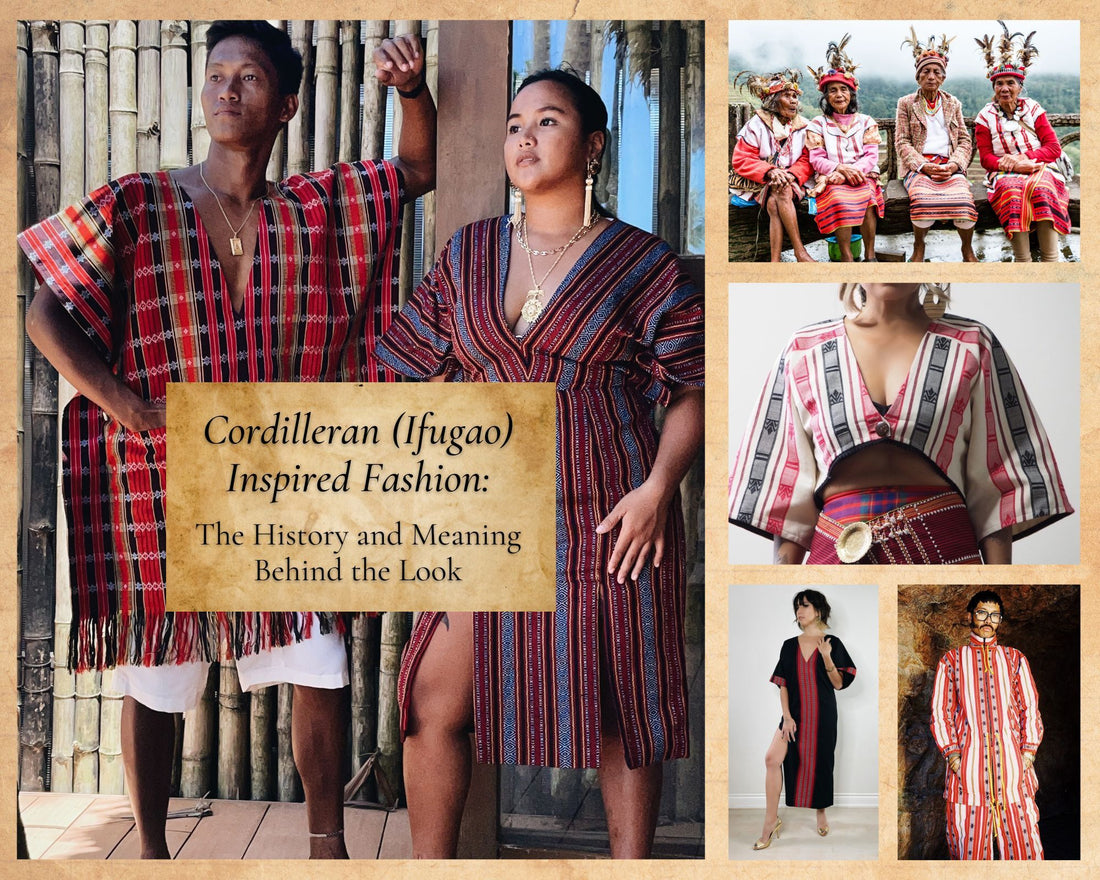

Cordilleran (Ifugao) Inspired Fashion: The History and Meaning Behind the Look

“I hate the idea of Filipino cultural clothing being a ‘costume.’ What are we, dressing up for Halloween as Filipinos, or are we Filipinos?”

When our founder, Caroline Mangosing, began research and development for VINTA Gallery back in 2009, her vision from the get-go was to do away with the idea of Filipino clothing always being associated with “costumes.” She wanted to create a fashionable Filipiniana clothing line that anybody can fit into their regular wardrobe or wear to a glammed-up party or event.

Since then, VINTA Gallery has created bespoke wedding dresses, terno tops with a variety of different styles and patterns, terno dresses with traditional butterfly sleeves (perfect for wedding guests), women’s barongs and barong dresses, one-of-a-kind terno jumpsuits, Filipiniana streetwear, modern camisas and more. But no other kind of Filipiniana clothing from VINTA Gallery has ever been as popular as our pan-Cordilleran / Ifugao pieces.

To be honest, it’s been tricky to keep up with the demand for all things Ifugao in our shop. As soon as we announce the restock of, say, our Ifugao Bahag Dress, it sells out in a matter of days (we’re feeling the love!). And as much as we hate to disappoint our loyal VINTA Gallery customers, in keeping with our slow fashion mission, we would never want to go into “factory mode” and produce more just to keep up — at the end of the day, we’re still going to make our products in limited quantities, so that each Ifugao style will only have about 10 or so pieces, depending on the intricacy and availability of the fabric.

To be honest, it’s been tricky to keep up with the demand for all things Ifugao in our shop. As soon as we announce the restock of, say, our Ifugao Bahag Dress, it sells out in a matter of days (we’re feeling the love!). And as much as we hate to disappoint our loyal VINTA Gallery customers, in keeping with our slow fashion mission, we would never want to go into “factory mode” and produce more just to keep up — at the end of the day, we’re still going to make our products in limited quantities, so that each Ifugao style will only have about 10 or so pieces, depending on the intricacy and availability of the fabric.So what’s the deal behind the new interest in Ifugao? There’s definitely a resurgence of the use of traditional textiles in modern fashion in general. For VINTA Gallery, we never anticipated this much enthusiasm and demand for our Ifugao items. From our Ifugao dresses and skirts to our Ifugao face masks and tops, we’re seeing these particular handloomed pieces have such an emotional impact with people who come across it — more so than any other items we carry in our store.

In speaking with past VINTA Gallery customers, many of them simply connect with Ifugao clothing, especially upon learning its history, its deep spiritual roots and the story behind its people. Ifugao fabrics are also very flattering to wear, but apart from that, it becomes more than just about the aesthetic — they feel as though they’re literally wearing their culture on their sleeve.

Back in December 2019, when we held VINTA’s first-ever Private Shopping Experience with Caroline, our contest winner Yasmine Faith, as she wore our Ifugao Anorak Jacket and Track Pants, spoke about her learnings and the “hundreds of years of resilience and tradition passed down generations in a single thread — the power and beauty that holds.” Very well said.

It’s exciting for us to see that customers and visitors to the website are doing their research and sharing their fascination and knowledge about Ifugao weaves, especially among Filipinx who grew up outside of the Philippines.

We’ve had a few curious followers ask us for more info about Ifugao — so let’s go on a journey behind its rich culture and origins and the meaning behind the patterns and symbols stitched onto these wonderful Ifugao fabrics.

What Exactly is Ifugao?

When we say “Ifugao,” we’re referring to the landlocked province of the Philippines in the Cordilleras region in northern Luzon where the handloomed traditional weave comes from. Have you ever seen images of these stunning rice terraces cascading across a beautiful mountain range somewhere in the Philippines? If yes, it’s most likely one of the most popular tourist attractions in the country, occasionally referred to as the “Eighth Wonder of the World” — the Banaue Rice Terraces.

These rice terraces were believed to be hand-carved into the mountains centuries before the start of European colonization (that’s over 4,000 miles of landscape). The Ifugao people also formed an intricate system of waterways, where water from the high mountains was filtered to the lower terraces, creating more rice cultivation — one of the best agricultural technologies in Asia at that time.

Who are the Ifugao People?

When referring to the tribe, Ifugao is named after the term i-pugo (“i” meaning from/people and “pugo” meaning hill), which literally translates to “people of the hill.” It may also mean “mortals” or “inhabitants of the known earth,” so they distinguished themselves from spirits and deities.

It is said that Ifugao people are quite possibly the oldest residents of the highlands, their origin dating back as early as 800-500 BC. What’s unique about the Ifugao was that they were one of the few peoples in the Archipelago least influenced by the Europeans and Americans. The Ifugao tribes battled colonizers for hundreds of years, and they managed to remain untouched by the influences of colonialism, due in part to the fierceness of their beliefs and their strength in political and economic resources. Because of this, Ifugao tribes were able to hold on to their traditional values and legal systems, with its social organization based almost exclusively on kinship, valuing family ties, spirituality and culture above all else. They are the very definition of resilience.

The women of Ifugao. Photo: Annapurna Mellor from Remotelands.com

In regards to their livelihood, agricultural terracing and farming were their primary means, with their social status determined by the amount of rice field granaries they had, carabaos, family heirlooms and overall prestige, which came with time. The kadangyan (a.k.a. the more affluent) were still very generous, giving their rice to their poor neighbours during any shortages.

The Ifugao people’s religion and spiritual rituals were unique to the Philippines, as many embraced Christianity as their main belief system. Unlike the Roman Catholic majority of most of the Filipino population, Ifugao people had an elaborate cosmology and belief in thousands of gods. The Ifugao traditionally believed their lives were ruled by spirits called anitos and that the universe was divided into levels — the top being the heavens (which itself had four “superimposed heavens”), Pugao (earth or “the known land”) and the underworld. There was no one supreme God, as the Ifugao acknowledged more than 1,500 spirits, each having specific roles and duties and covering almost every aspect of life, such as war, peace, fishing, rain — you get the picture.

Probably one of the most iconic and recognizable images of the Ifugao religion are bu’luls — totemic male and female figures carved in wood, used in rituals and as guardian figures. The bulul was believed to guard the rice crop and gain power from the presence of the ancestral spirit, but it also represented the hundreds of spirits, deities and ancestors that populated the Ifugao’s concept of the universe.

Apart from their deep and unwavering spiritual beliefs, a little known fact was that the Ifugao were previously feared as headhunters, with their war-dance (the bangibang) being one of the cultural remnants of the time of tribal conflict. This dance was traditionally held on the walls of the rice terraces, with the men decked out in traditional loincloths and fierce headdresses, spears, axes and wooden shields in hand. Cornelis De Witt Willcox writes more about the dance in great detail, including Ifugao revenge councils (!!) and vengeance feasts at tribal funerals, in “The Head Hunters of Northern Luzon” — read some of the excerpts here.

Other features unique to the Ifugao were their narrative literature, such as the hudhud (an epic revolving around hero ancestors and sung in a poetic style), their wood-carving art, mostly of spiritual guardians, and of course, their textiles.

VINTA Gallery’s Ifugao-inspired Fashion

Without a doubt, Ifugao textiles are renowned for their sheer beauty, bright colours and unique patterns — but they also represent so much more. Artisans by nature, Ifugao fabrics are hand-woven on looms using traditional, age-old techniques passed on through generations. It’s an elaborate process with many stages that requires patience, skill and attention to detail.

Many of our VINTA Gallery pieces were inspired by the incredible women of this unique and resilient tribe. Ifugao women have traditionally worn short, tight-fitting, hand-woven skirts with colourful stripes. Our Ifugao Bahag Dress, made from handloomed traditional Ifugao stripe textile, is inspired by the bahag of the Cordillera region. Bahag is a loincloth commonly used by the Ifugao people and other indigenous tribes in the Cordilleras region in northern Luzon, usually wrapped from behind with the longer piece of cloth draped down the middle front.

While today, cloth is primarily used, earlier versions of the bahag were created from tree bark or dried banana leaves — a long process to make, as it involved cutting the bark, beating it down to loosen it, soaking, whipping with a club to make it soft and then drying in the sun, as William Henry Scott explains in his book, A Sagada Reader.

While the main use of the bahag was to cover and protect the wearer from the elements, it was also used to distinguish members of the community. The greater the colour combinations and more elaborate the designs, the higher your status was. In the past, it also distinguished hunters from healers, the old from the young and kin from friends. The bahag was a major part of the Ifugao’s personality, story and pride.

On a few of the VINTA Gallery pieces, there are small symbols stitched into the fabric that carry a deeper meaning. If you look closely, our Paracelis Face Mask has a helix-like structure weaved into the fabric, which refers to the lightning god a.k.a. the messenger god. This symbol is used to signal mortal's efforts to reach their superior gods, as one would need the help of the messenger god to talk to the higher gods. Though Paracelis is not technically Ifugao — it is a town that borders the Ifugao provinces — it shares similar beliefs with the Ifugao.

Now for the Tough Questions… The Issue of Cultural Appropriation

We’ve gotten super creative with these gorgeous pieces of fabric, coming up with modern interpretations of traditional pieces, such as VINTA fan favourite, The Unisex Handloomed Belted Poncho, with Kalinga-inspired modern weaves designed by the talented folx at Ifugao Nation.

But is it okay to wear indigenous Ifugao weaves if we’re not from Ifugao? We’ve had this question asked many times, and rightfully so.

In a past “Ask Me Anything” Instagram session with our founder Caroline, one question from our followers stood out among the rest: “How do you navigate concerns of appropriation when working with indigenous groups and textiles, e.g. Tagalogs wearing Ifugao prints, wearing tribes that you don’t claim/have any relationship with?” Great question.

When considering purchasing any pieces of clothing made with native weaves, it’s critical to know whether you are appropriating a culture — an issue that doesn’t often come to mind when consumers support local brands and slow fashion.

“Cultural appropriation is defined as the unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices and ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society,” Caroline explained in her response. The Ifugao Heritage School goes on to say cultural appropriation is when you claim another culture as your own, when you’re unaware of the context of the cultural property you’re using, and ultimately disrespecting a culture. It all comes down to knowing about what you’re buying and wearing before putting them on.

At VINTA Gallery, we source our indigenous textiles directly or indirectly, through organizations such as Ifugao Nation and the Manila Collectible Company that ethically support weaving communities in the Philippines, so what we are doing acknowledges the people whose hands make the textiles. We try to give as much information and transparency as possible in our product descriptions, social media channels and email inquiries from our customers, so that we can not only credit the source, but also so that we can provide essential details about the fabric’s origins, fuelling our customer with the knowledge they need to understand and respect the native textiles they’re wearing.

We provide a regional context for every piece we create in an effort to educate and expose more of our culture to the Filipino diaspora and beyond. These older ways of weaving and wearing garments have inspired us to make one-of-a-kind pieces, so we could pay homage to these traditional styles. More importantly, as mentioned, we aim to support local weavers and provide a living wage for the VINTA Gallery skilled artisans who make our products.

Certain Ifugao weave designs are made to be sold to buyers in Manila. Photo taken from Rappler in a great article: "5 things to ask before buying indigenous weaves"

“The Ifugao weaves are made by Ifugao people — we buy them directly from that region or through a retailer,” Caroline continues. “The people who weave the fabric sell it for their livelihood, bottom line. When we sell the garments made with that weave, we call it what it is in the product description on our website. Individuals who wear it bear the responsibility of naming what they are wearing. The wearer can (should) choose to engage with others about what they know about Ifugao people. I think that is the beauty of sharing the culture.”

It’s also important to understand what the designs and patterns mean. One issue with some brands using these indigenous weaves for fashionable items is that many of the textiles often get lost in translation. For example, using and altering a specific and symbolic handloomed blanket as fabric for a skirt, when in fact it’s a ga’mong (“blanket for the dead” used strictly for funerals), is very disrespectful to the culture. So designers and clothing brands bear the responsibility of understanding what these fabrics represent, how these pieces reflect Ifugao religions, their roots and the people’s resistance before purchasing and modifying into their modern interpretation.

At the end of the day, VINTA strives to create those important, and sometimes uncomfortable, conversations about the traditional textiles, where its from, its heritage and history of the indigenous Philippines — a topic that should and needs to be revived, so that we could come to understand the healing and growth of an often neglected people. Proudly wearing these pieces in one’s everyday life can help to introduce the Ifugao culture to the greater Filipinx community in a new and positive light.

“I believe it is particularly important for the diasporic Filipinxs (whether they are Tagalogs or Visayan) to educate themselves on the systemic oppression of indigenous tribes in the Philippines — it is rampant, like all indigenous groups all over the world,” Caroline said. “And contribute to fight the oppressor in any way they can.”